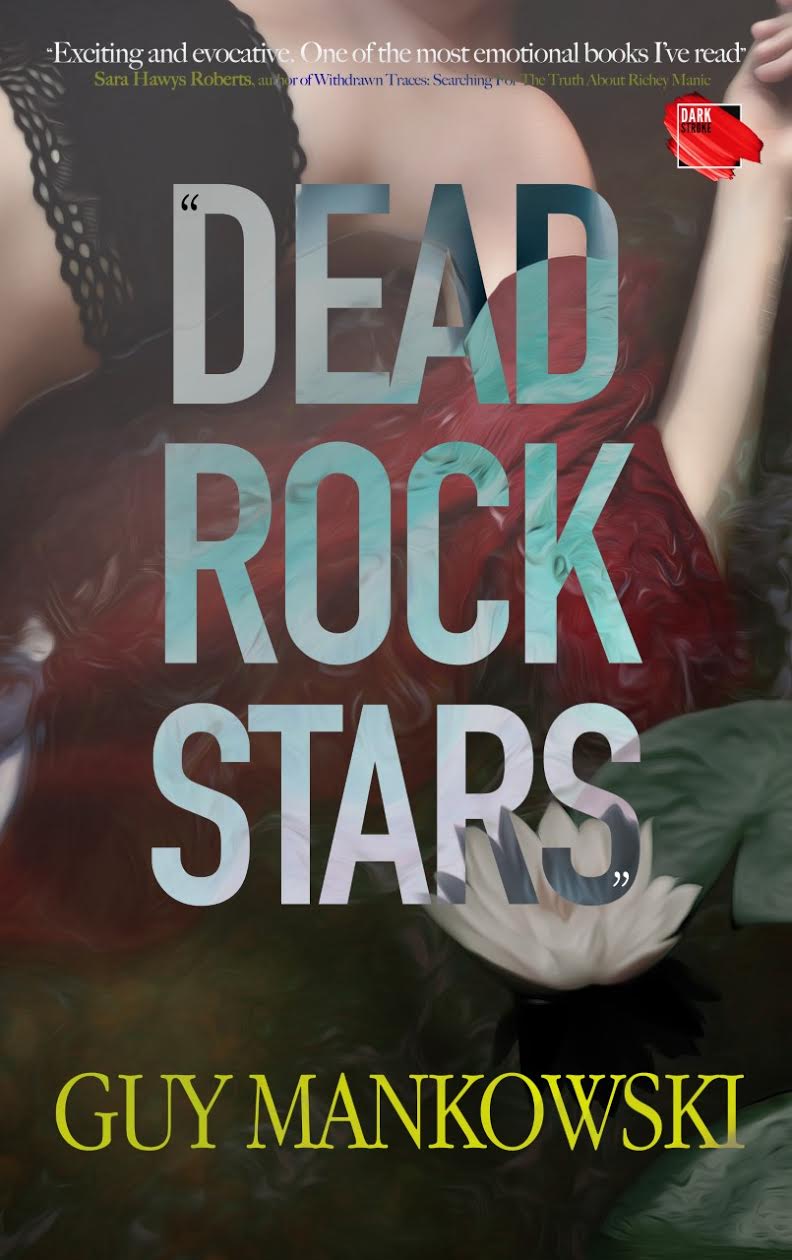

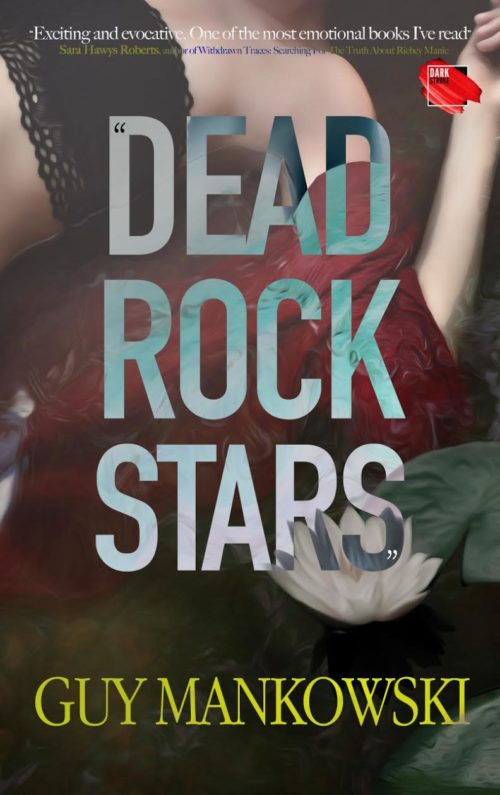

Guy Mankowski: Dead Rock Stars

I’m very pleased to welcome Guy Mankowski to my blog today – Guy is a fellow darkstroke author and he is also a musician, with some very cool band credentials. Guy was singer in the signed band Alba Nova, and went on to play guitar in bands like The Beautiful Machine. His novels include ‘The Intimates’ (a 2011 Read Regional Title), ‘Letters from Yelena’ (winner of an Arts Council Literature award & featured in GCSE training by Osiris Educational), ‘How I Left The National Grid’ (written as part of a PhD in Creative Writing) and ‘An Honest Deceit’ (winner of an Arts Council Literature Award and a New Writing North Read Regional Award). He is a full time lecturer at The University of Lincoln.

‘Dead Rock Stars’ was published on 14th September 2020 and is available HERE:

With its Nineties-inspired playlist available on Youtube and Spotify

‘All we love is lonely wreckage’. As a former Manics fan (more into the glitter and tiaras than their later stadium rock) I have an unremitting appetite for cultural detritus left by the bands I loved. When it comes to those groups and the eras from which these bands were spawned any evidence of the glamour of their past existence fascinates me. The Manics, My Vitriol, King Adora. The higher and more ridiculous the bands ambitions the more fascination I find in their wake. My new novel, “Dead Rock Stars” builds on the preoccupation with fandom in my previous book How I Left The National Grid and takes it to new levels. For “Dead Rock Stars” I invented a Kinderwhore band (Cherub) that didn’t exist. Cherub, with ballerina box merchandise and marble vinyl and their songs (sample titles- “Ruined Beauty Pageant”, “The Sculptress” and “Namedropper”) are perched on the edge of fame, an infighting Grrrl group, a defiant cartoon-like bubble of fake fur, leopard print and glitter in the era of Camden toxic masculinity. Their lead singer, Emma, is drawn into the heart of this London-centric world, with fatal consequence. Much of the novel is concerned with her lost diary entries, as her brother reads her journal and tries to pick up the pieces regarding what befell her. The novel contains fake reviews of her bands, and I had fun capturing the hyperbole of the nineties music weeklies (Emma’s song “Hairy Food” is described in one fake Melody Maker review within the novel as depicting ‘a grunge goldilocks for the twentieth century’).

I’m fascinated by the concept of ‘Parasocial Interaction’- a term which originated from the psychologists Donald Horton and Richard Wohl. They looked at the interactive nature of celebrity culture in the era of postmodern media. Their theory suggests that a stars ‘emotive performance can misleadingly invite the audience to believe that they really knew him or her’, in the words of the academic Paula Hearsum. I think that in writing this novel I was attempting to dismantle the 90’s star making machine, and construct a star with which I could have such an interaction. In many ways the book is a glitter-smeared love letter to an era of mix tapes and music weeklies. At one point Emma’s brother, Jeff, sifts through the cheap cassette bin in his newsagents in much the way I used to, looking for his lost sister’s lost album. He is barely sure it exists. In his will to find it he repeatedly thinks he has discovered a copy, when in fact instead he is finding cassettes by other bands, with their aesthetic similar enough for him to hallucinate, in a grief-stricken, dreamlike manner, that he has unearthed a lost fragment of his sister. What I find fascinating about this era of cultural artefacts (where the cassette, the multiple CD versions of singles and music weeklies reigned supreme) was how many ways artists had to flesh out their vision. If Select magazine released posters with an issue, many teenagers like me existed within the hegemony of those six choices by which to adorn our walls. If the NME gave an album five stars or a coveted cover position then, overnight, they became famous. The much-loved Suede evidence this, becoming as surprised as anyone when they became famous without knowing it.

I’m particularly fascinated by the unfairness of the way women musicians were overlooked in this era. As a huge Nirvana fan, the way that Hole bassist Kristen Pfaff’s death was overshadowed by that of Kurt Cobain exemplifies this unfairness. Hearsum identifies a hierarchy in which different stars apparently deserved ‘more grief’ depending on their mode of death. Relative to Kirsty MacColl or Aaliyah, the drugs implicated in Pfaff’s death led to an unfair dismissal of her rich musical legacy, as a leading light of the band Janitor Joe as well as Hole. Similarly, the apparent reckless living of Amy Winehouse casts a mean-spirited shadow over critical appraisal of her work.

The psychologist Edwin Shneidman coined the term ‘psychological autopsy’, for coroners looking to consider if a death is accidental or deliberate. It’s a term that first came into parlance during such examinations into the death of Marilyn Monroe, by the psychiatrist Robert Litman, and it’s an approach later used to examine the passing of Elvis Presley. In the words of Hearsum the ‘psychological autopsy’ uses ‘interviews with family, friends, associates and other documents from the deceased person to try and construct their state of mind.’ In my novel, Emma’s brother Jeff is doing just this, excavating his sisters lost pop videos, journals, artwork, lyrics and reviews, through a meditative practice of solitude to try and work out what happened to her.

Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie cleverly captured this sense of culture as hauntological, in their series Phonogram: Rue Britannia. Its protagonist, David Kohl, is a cynical former fan of Britpop, represented by goddess named Britannia. The series contains a character called Beth, who remains stuck outside of time in her adolescent persona as a Manics fan. She is eyeliner smeared, boa-wearing ghost. When we meet the present Beth we see how she has abandoned the stereotypical features of the Manics fan. Larissa Wodtke describes her as ‘a consignment of memories, an exterior archive.’ It is curious to think of our past teenage selves as this, ephemeral and enduring, utterly redundant in the present and yet potent enough to feel primed for re-activation.

Jeff’s attempt to re-activate and assimilate his sisters past is made all the more bizarre by the ephemeral nature of the detritus of the era in which his sister thrived. An era in which reviews in Melody Maker could bestow fame, but were also written in hyperbolic language that strayed close to the nonsensical. In his excellent book The Last Party John Harris summarises this tendency in a quote from the long-department band Truman, who were described in one review as ‘brilliantly rubbish.’ A copy of Melody Maker might come with free comic postcards of Brian Molko on the beach, but five stars from them would still change your life.

The reportage in that era wasn’t just hyperbolic, it was often vicious. Steven Wells famously described indie bedwetters Los Campesinos! (that exclamation mark!) as ‘a 14-legged abortion’- which would be a career ending description for him today. In the music weeklies there were features in which this spitefulness became a habit. Holly Hernandez’s weekly column in Melody Maker, ‘Holly’s Demo Hell’ skewered the aspirations of rock star wannabes with its dismissiveness, (‘lack of talent abounds’ runs one review I found) in a magazine which pages earlier scrutinised with earnest sincerity the Planet Of The Apes based plotline of Gay Dad’s last single. Hernandez was not alone in this bitchy approach during this era. Karen Krizanovich, in the relatively unmourned Sky Magazine (lite porn masquerading as harmless TV listings) would also dispense black hearted mockery in the guise of an agony aunt under a comparably foxy persona. Seemingly friendly characters, such as Mr Agreeable, pop up in corners of the pages of Melody Maker to rant with splenetic poison at Roger Daltrey’s new project (‘I’d rather eat an infected pigs bladder than listen to this shit’).

In an era in which there seems a real lack of counter-culture, let alone a lack of physical evidence of it, I hope this book will be a postcard to an era that I sorely miss. When culture, no matter how cheaply printed, seemed to have more presence.

‘The first page of my sister’s diary was a picture of Frances Farmer, facing a drawing of Ophelia. My sister’s psychic accomplices were all tragic figures…’

Emma Imrie was a Plath-obsessed, self-taught teenage musician dreaming of fame, from a remote village on the Isle of Wight. She found it too, briefly becoming a star of the nineties Camden music scene. But then she died in mysterious circumstances.

In the aftermath of Emma’s death, her younger brother, Jeff, is forced by their parents to stay at the opulent home of childhood friends on the island.

During a wild summer of beach parties and music, Jeff faces up to the challenges that come with young love, youthful ambition and unresolved grief. His sister’s prodigious advice from beyond the grave becomes the only weapon he has against an indifferent world.

As well as the only place where the answers he craves might exist…

“Dead Rock Stars” is published on 14th September and is available to buy HERE

With its Nineties-inspired playlist available here:

Dead Rock Stars Youtube playlist

Dead Rock Stars Spotify playlist

Personal links:

Instagram @guymankowski

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/guymankowskiauthor/

Twitter @Gmankow